- Home

- John Irving

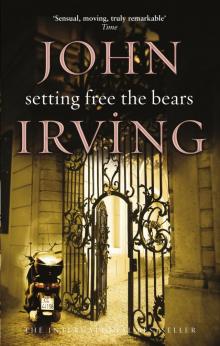

Setting Free the Bears

Setting Free the Bears Read online

About the Book

It is 1967 and two Viennese university students decide to liberate the Vienna Zoo, as was done after World War II. The eccentric duo, Graff and Siggy, embark on an adventure-filled motorbike tour of Austria as they prepare for 'the great zoo bust.' But their grand scheme will have both comic and gruesome consequences, as they are soon to find out...

CONTENTS

Cover

About the Book

Title Page

Dedication

PART ONE: SIGGY

A Steady Diet in Vienna

Hard Times

The Beast Beneath Me

Herr Faber's Beast

Fine Tuning

The First Act of God

God Works in Strange Ways

The Hippohouse

Drawing the Line

Night Riders

Living Off the Land

Where the Walruses Are

Going Nowhere

Going Somewhere

Fairies All Around

The Second Sweet Act of God

Great Bear, Big Dipper, The Ways Are Strange Indeed

What All of Us Were Waiting For

Cared For

Out of the Bathtub, Life Goes On

Off the Scent

The Foot of Your Bed

A Blurb from the Prophet

What Christ Cooked Up in the Bathroom

Massing the Forces of Justice

The Revealing of Crimes

Fetching the Details

The Real and Unreasonable World

Looking Out

Speculations

The Approach of the Veritable Pin

Fate's Disguise

Faith

Denying the Animal

How Many Bees Would Do for You?

Uphill and Downhill, Hither and Yon

The Number of Bees That Will Do

PART TWO: THE NOTEBOOK

The First Zoo Watch: Monday, 5 June 1967 @ 1:20 p.m.

The Second Zoo Watch: Monday, 5 June 1967 @ 4.30 p.m.

The Third Zoo Watch: Monday, 5 June 1967, @ 7.30 p.m.

The Fourth Zoo Watch: Monday, 5 June 1967 @ 9.00 p.m.

The Fifth Zoo Watch: Monday, 5 June 1967 @ 11.45 p.m.

The Sixth Zoo Watch: Tuesday, 6 June 1967 @ 1.30 a.m.

The Seventh Zoo Watch: Tuesday, 6 June 1967, @ 2.15 a.m.

The Eighth Zoo Watch: Tuesday, 6 June 1967, @ 3.00 a.m.

The Ninth Zoo Watch: Tuesday, 6 June 1967, @ 3.15 a.m.

The Tenth Zoo Watch: Tuesday, 6 June 1967, @ 3.45 a.m.

The Eleventh Zoo Watch: Tuesday 6 June, 1967, @ 4.15 a.m.

The Twelfth Zoo Watch: Tuesday, 6 June 1967, @ 4.30 a.m.

The Thirteenth Zoo Watch: Tuesday, 6 June 1967, @ 4.45 a.m.

The Fourteenth Zoo Watch: Tuesday, 6 June, 1967, @ 5.00 a.m.

The Fifteenth Zoo Watch: Tuesday, 6 June 1967, @ 5.15 a.m.

The Sixteenth Zoo Watch: Tuesday, 6 June 1967, @ 5.30 a.m.

The Seventeenth Zoo Watch: Tuesday, 6 June 1967, @ 5.45 a.m.

The Eighteenth Zoo Watch: Tuesday, 6 June 1967, @ 6.00 a.m.

The Nineteenth Zoo Watch: Tuesday, 6 June 1967, @ 6.15 a.m.

The Twentieth Zoo Watch: Tuesday, 6 June 1967, @ 6.30 a.m.

The Twenty-First Zoo Watch: Tuesday, 6 June 1967, @ 6.45 a.m.

The Twenty-Second and Very Last Zoo Watch: Tuesday, 6 June 1967, @ 7.30 a.m.

PART THREE: SETTING THEM FREE

P.S.

Loose Ends

Where Gallen Was

What Keff Was Doing

What Ernst Watzek-Trummer Received by Mail

What Keff Also Did

The Feel of the Night

What Gallen Did, Finally

What Gallen Did, Again

Noah's Ark

Plans

More Plans

How the Animals' Radar Marked my Re-entry

How, Clearing the Ditch, I Fell in the Gorge

Following Directions

First Things First

My Reunion with the Real and Unreasonable World

Making New Plans

Congratulations to All You Survivors!

In One Person Extract

About the Author

Also by John Irving

Copyright

SETTING FREE

THE BEARS

John Irving

This book is for

VIOLETTE and CO

in memory of

GEORGE

Part One

Siggy

A Steady Diet in Vienna

I COULD FIND him every noon, sitting on a bench in the Rathaus Park with a small, fat bag of hothouse radishes in his lap and a bottle of beer in one hand. He always brought his own saltshaker; he must have had a great number of them, because I can't recall a particular one from the lot. They were never very fancy saltshakers, though, and once he even threw one away; he just wrapped it up in the empty radishbag and tossed it in one of the park's trashcans.

Every noon, and always the same bench - the least splintery one, on the edge of the park nearest the university. Occasionally he had a notebook with him, but always the corduroy duckhunter's jacket with its side slash-pockets, and the great vent-pocket at the back. The radishes, the bottle of beer, a saltshaker, and sometimes the notebook - all of them from the long, bulging vent-pocket. He carried nothing in his hands when he walked. His tobacco and pipes went in the side slash-pockets of the jacket; he had at least three different pipes.

Although I assumed he was a student like myself, I hadn't seen him in any of the university buildings. Only in the Rathaus Park, every noon of the new spring days. Often I sat on the bench opposite him while he ate. I'd have my newspaper, and it was a fine spot to watch the girls come along the walk; you could peek at their pale, winter knees - the hardboned, blousy girls in their diaphanous silks. But he didn't watch them; he just perched as alertly as a squirrel over the bag of radishes. Through the bench slats, the sun zebra-striped his lap.

I'd had more than a week of such contact with him before I noticed another of his habits. He scribbled things on the radishbag, and he was always stashing little pieces of bag in his pockets, but more often he wrote in the notebook.

One day he did this: I saw him pocket a little note on a bag piece, walk away from the bench, and a bit down the path decide to have another look. He pulled out the bag piece and read it. Then he threw it away, and this is what I read:

The fanatical maintenance of good habits is necessary.

It was later, when I read his famous notebook - his Poetry, as he spoke of it - that I realized this note hadn't been entirely thrown away. He'd simply cleaned it a little.

Good habits are worth being fanatical about.

But back in the Rathaus Park, with the little scrap from the radishbag, I couldn't tell he was a poet and a maxim-maker; I only thought he'd be an interesting fellow to know.

Hard Times

THERE'S A PLACE on Josefsgasse, behind the Parliament Building, known for its fast, suspicious turnover of second-hand motorcycles. I've Doktor Ficht to thank for my discovery of the place. It was Doktor Ficht's exam I'd just flunked, which put me in a mood to vary my usual noon habit in the Rathaus Park.

I went off through a number of little arches with boggy smells, past cellar stores with mildewy clothes and into a section of garages - tire shops and auto-parts places, where smudged men in overalls were clanking and rolling things out on the sidewalk. I came on it suddenly, a dirty showcase window with the cardboard sign FABER'S in a corner of glass; nothing more in the way of advertising, except the noise spuming from an open doorway. Fumes dark as thunderclouds, an upstarting series of blatting echo-shots, and t

hrough the showcase window I could make out the two mechanics racing the throttles of two motorcycles; there were more motorcycles on the platform nearest the window but these were shiny and still. Scattered about on the cement floor by the doorway, and blurred in exhaust, were various tools and gas-tank caps - pieces of spoke and wheel rim, fender and cable - and these two intent mechanics bent over their cycles; playing the throttles up and down, they looked as serious and ear-ready as any musicians tuning up for a show. I inhaled from the doorway.

Watching me, just inside, was a gray man with wide, oily lapels; the buttons were the dullest part of his suit. A great sprocket leaned against the doorway beside him - a fallen, sawtoothed moon, so heavy with grease it absorbed light and glowed at me.

'Herr Faber himself,' the man said, prodding his chest with his thumb. And he ushered me out the doorway and back down the street. When we were away from the din, he studied me with a tiny, gold-capped smile.

'Ah!' he said. 'The university?'

'God willing,' I said, 'but it's unlikely.'

'Fallen in hard times?' said Herr Faber. 'What sort of a motorcycle did you have in mind?'

'I don't have anything in mind,' I told him.

'Oh,' said Faber, 'it's never easy to decide.'

'It's staggering,' I said.

'Oh, don't I know?' he said. 'Some bikes are such animals beneath you, really - veritable beasts! And that's exactly what some have in mind. Just what they're looking for!'

'It makes you giddy to think of it,' I said.

'I agree, I agree,' said Herr Faber. 'I know just what you mean. You should talk with Herr Javotnik. He's a student - like yourself! And he'll be back from lunch presently. Herr Javotnik is a wonder at helping people make up their minds. A virtuoso with decisions!'

'Amazing,' I said.

'And a joy and a comfort to me,' he said. 'You'll see.' Herr Faber cocked his slippery head to one side and listened lovingly to the burt, burt, burt of the motorcycles within.

The Beast Beneath Me

I RECOGNIZED HERR JAVOTNIK by his corduroy duckhunter's jacket with the pipes protruding from the side slash-pockets. He looked like a young man coming from a lunch that had left his mouth salty and stinging.

'Ah!' said Herr Faber, and he took two little side steps as if he would do a dance for us. 'Herr Javotnik,' he said, 'this young man has a decision to make.'

'So that's it,' said Javotnik, '--why you weren't in the park?'

'Ah! Ah?' Herr Faber squealed. 'You know each other?'

'Very well,' Javotnik said. 'I should say, very well. This will be a most personal decision, I'm sure, Herr Faber. If you'd leave us.'

'Well, yes,' said Faber. 'Very well, very well' - and he sidled away from us, returning to the exhaust in his doorway.

'A lout, of course,' said Javotnik. 'You've no mind to buy a thing, have you?'

'No,' I said. 'I just happened along.'

'Strange not to see you in the park.'

'I've fallen in hard times,' I told him.

'Whose exam?' he asked.

'Ficht's.'

'Well, Ficht. I can tell you a bit about him. He's got rotten gums, uses a little brush between his classes - swabs his gums with some gunk from a brown jar. His breath could wilt a weed. He's fallen in hard times himself.'

'It's good to know,' I said.

'But you've no interest in motorcycles?' he asked. 'I've an interest myself, just to hop on one and leave this city. Vienna's no spot for the spring, really. But, of course, I couldn't go more than half toward any bike in there.'

'I couldn't either,' I said.

'That so?' he said. 'What's your name?'

'Graff,' I told him. 'Hannes Graff.'

'Well, Graff, there's one especially nice motorcycle in there, if you've any thoughts toward a trip.'

'Well,' I said, 'I couldn't go more than half, you know, and it seems you're tied up with a job.'

'I'm never tied up,' said Javotnik.

'But perhaps you've gotten in the habit,' I told him. 'Habits aren't to be scoffed at, you know.' And he braced back on his heels a moment, brought up a pipe from his jacket and clacked it against his teeth.

'I'm all for a good whim too,' he said. 'My name's Siggy. Siegfried Javotnik.'

And although he made no note of it at the time, he would later add this idea to his notebook, under the revised line concerning habit and fanaticism - this new maxim also rephrased.

Be blissfully guided by the veritable urge!

But that afternoon on the sidewalk he was perhaps without his notebook or a scrap of radishbag, and he must have felt the prompting of Herr Faber, who peered so anxiously at us, his head darting like a snake's tongue out of the smoggy garage.

'Come with me, Graff,' said Siggy. 'I'm going to sit you on a beast.'

So we crossed the slick floor of the garage to a door against the back wall, a door with a dartboard on it; both the door and the dartboard hung askew. The dartboard was all chewed up, the bull's-eye indistinguishable from the matted clots of cork all over - as if it had been attacked with wrenches instead of darts, or by mad mechanics with tearing mouths.

We went out into an alley behind the garage.

'Oh now, Herr Javotnik,' said Faber. 'Do you really think so?'

'Absolutely,' said Siegfried Javotnik.

It was covered with a glossy black tarp and leaned against the wall of the garage. The rear fender was as thick as my finger, a heavy chunk of chrome, gray on the rim where it took some of the color from the mudcleats, deep-grooved on the rear tire - tire and fender and the perfect gap between. Siggy pulled the tarp off.

It was an old, cruel-looking motorcycle, missing the gentle lines and the filled-in places; it had spaces in between its parts, a gap where some clutterer might have tried to put a toolbox, a little open triangle between the engine and the gas tank too - the tank, a sleek teardrop of black, sat like a too small head on a bulky body; it was lovely like a gun is sometimes lovely - for the obvious, ugly function showing in its most prominent parts. It weighed, all right, and seemed to suck its belly in, like a lean, hunched dog in the tall grass.

'A virtuoso, this boy!' Herr Faber said. 'A joy and a comfort.'

'It's British,' said Siggy. 'Royal Enfield, some years ago when they made the pieces look like the way they worked. Seven hundred cubic centimeters. New tires and chains, and the clutch has been rebuilt. Like new.'

'This boy, he loves this old one!' said Faber. 'He worked on it all on his own time. It's like new!'

'It's new, all right,' Siggy whispered. 'I ordered from London - new clutch and sprocket, new pistons and rings - and he thought it was for his other bikes. The old thief doesn't know what it's worth.'

'Sit on it!' Herr Faber said. 'Oh, just sit, and feel the beast beneath you!'

'Half and half,' whispered Siggy. 'You pay it all now, and I'll pay you back with my wages.'

'Start it up for me,' I said.

'Ah well,' said Faber. 'Herr Javotnik, it's not quite ready to start up now, is it? Maybe it needs gas.'

'Oh no,' said Siggy. 'It should start right up.' And he came alongside me and pumped on the kick starter; there was very little fiddling - a tickle to the carburetor, the spark retard out and back. Then he rose up beside me and dropped his weight on the kicker. The engine sucked and gasped, and the stick flew back against him; but he tramped it again, and quickly again, and this time it caught - not with the burting of the motorcycles inside: with a lower, steadier borp, borp, borp, as rich as a tractor.

'Hear that?' cried Herr Faber, who suddenly listened himself - his head tilting a bit, and his hand slicking over his mouth - as if he'd expected to hear a valve tapping, but didn't; expected to hear a certain roughness in the idle, but couldn't - at least, not quite. And his head tilted more.

'A virtuoso,' said Faber, who was beginning to sound as if he believed it.

Herr Faber's Beast

HERR FABER'S OFFICE WAS on the second floor of the garage, which

looked as if it couldn't have a second floor.

'A grim urinal of a place,' said Siggy, whose manners were making Herr Faber nervous.

'Have we set a price on that one?' Faber asked.

'Oh, yes we have,' said Siggy. 'Twenty-one hundred schillings, it was, Herr Faber.'

'Oh, a very good price,' said Faber in an unwell voice.

I paid.

'And might I trouble you further, Herr Faber?' said Siggy.

'Oh?' Faber moaned.

'Might you give me my wages up to today?' said Siggy.

'Oh, Herr Javotnik!' Faber said.

'Oh, Herr Faber,' said Siggy. 'Could you manage it?'

'You're a cruel schemer after an old man's money,' Faber said.

'Now, I've made some rare deals for you,' said Siggy.

'You're a dirty young cheating scheming bastard,' Herr Faber said.

'Do you see, Graff?' said Siggy. 'Oh, Herr Faber,' he said, 'I believe there's a veritable beast at home in your gentle heart.'

'Frotters!' Herr Faber shouted. 'Thieving frotters everywhere I turn!'

'If you could manage my wages,' said Siggy. 'If you could just do that, I'd be off with Graff here. We've got some fine tuning to do.'

'Ah!' Faber cried. 'That motorcycle doesn't need a bath!'

Fine Tuning

SO WE SAT in the evening at the Volksgarten Cafe and looked over the rock garden to the trees, and looked down in the pools of red and green water, reflecting the green and red lights strung over the terrace. The girls were all out; through the trees their voices came suddenly and thrillingly to us; like birds, girls in the city are always preceded by the noises they make - their heels on the walk, and their cock-sure voices confiding to each other.

'Well, Graff,' said Siggy, 'it's a blossom of a night.'

'It is,' I agreed - the first heavy night of the spring, with a damp, hard-to-remember heat in the air, and the girls with their arms bare again.

'We'll make it a zounds! of a trip,' said Siggy. 'I've thought about this for a long time, Graff, and I've got the way not to spoil it. No planning, Graff - that's the first thing. No mapping it out, no dates to get anywhere, no dates to get back. Just think of things! Think of mountains, say, or think of beaches. Think of rich widows and farm girls! Then just point to where you feel they'll be, and pick the roads the same way too - pick them for the curves and hills. That's the second thing - to pick roads that the beast will love.

'How do you like the motorcycle, Graff?' he asked.

'I love it,' I said, although he'd driven me on it no more than a few blocks, from Faber's round the Schmerlingplatz and over to the Volksgarten. It was a fine, loud, throbbing thing under you - sprang off from the stops like a great wary cat; even when it idled, the loathsome pedestrians never took their eyes off it.

My Movie Business: A Memoir

My Movie Business: A Memoir In One Person

In One Person Setting Free the Bears

Setting Free the Bears The Fourth Hand

The Fourth Hand The Imaginary Girlfriend

The Imaginary Girlfriend A Prayer for Owen Meany

A Prayer for Owen Meany A Son of the Circus

A Son of the Circus Last Night in Twisted River

Last Night in Twisted River The World According to Garp

The World According to Garp The Cider House Rules

The Cider House Rules The Hotel New Hampshire

The Hotel New Hampshire The 158-Pound Marriage

The 158-Pound Marriage Until I Find You

Until I Find You Trying to Save Piggy Sneed

Trying to Save Piggy Sneed Cider House Rules

Cider House Rules A Widow for One Year

A Widow for One Year A prayer for Owen Meany: a novel

A prayer for Owen Meany: a novel (2005) Until I Find You

(2005) Until I Find You